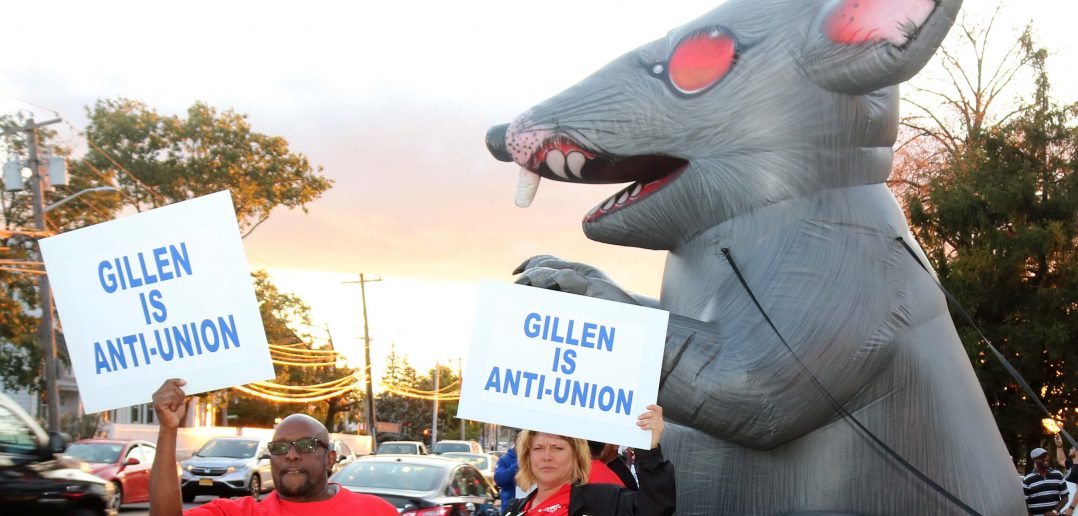

In this file photo, CSEA Hempstead Local member James Holly and CSEA Hempstead Local President Terry Kohutka protest at a rally in front of Hempstead Town Hall. Scabby the rat is in the background. (Photos by Wendi Bowie)

When CSEA and other union members demonstrate against an injustice, chances are that a large, inflatable rat nicknamed “Scabby” may be nearby.

But if the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) gets its way, Scabby could be eliminated, and union members’ rights to free speech could become the bait.

The board, which is controlled by Trump administration appointees who generally don’t side with labor, is fighting to ban the use of not only Scabby, but also inflatable friends such as ‘Fat Cat’ and ‘Greedy Pig,’ from union rallies, claiming the symbols are distracting and coercive and not a protected form of speech under the First Amendment.

While the NLRB covers only private-sector employers, a court ruling against the use of the rat could have far-reaching implications not just on unions’ ability to use such symbols, but on more broad-reaching First Amendment and labor rights.

“This move by the NLRB is yet another way for billionaires and anti-labor groups to attack working people,” CSEA President Mary E. Sullivan said. “No matter what the board and the courts decide, union members won’t be silenced.”

What is Scabby?

Scabby, who is believed to have first appeared in Chicago about 30 years ago, is usually between 6 to 25 feet tall and sports a pink, scab-infested stomach, a gray body frame and sharp claws, all intended to symbolize employers and their unfair treatment of workers.

Similarly, Fat Cat is often depicted as wearing a suit and sporting a cigar in its mouth and holding wads of money, while Greedy Pig is portrayed as wearing an ill-fitting suit and having wads of cash in its pockets.

Scabby is used by union members across the country, including many CSEA locals and units, during many demonstrations. The rat is considered an effective tool for unions in communicating injustices in numerous labor issues due to its imposing presence in public areas.

Morris Ware Jr. lets Town of Hempstead residents know the poor treatment workers receive at the hands of the town supervisor.

Why some want Scabby banned

While Scabby is noticeable and effective, the NLRB has been moving to deflate him in recent months.

Current board members have filed memos and are pursuing court action over the rat, calling its presence ‘coercive’ and noting that the symbols constitute illegal picketing.

The recent filings stem from several labor cases across the country, including one at a supermarket construction site on Staten Island. Laborers Local 79 used Scabby to protest the company’s use of non-union labor. The owner filed an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB against the union leading that protest.

The labor board in turn asked a federal court to bar the union from using the icons. While the court denied the request, the NLRB has appealed.

The board is also pursuing actions against the rat in several other cities across the country.

It’s not the first time Scabby has come under fire before the labor board; employers have brought complaints before the board numerous times over the years.

Courts have generally sided with unions in deeming Scabby as a protected form of speech, and the NLRB had previously followed suit, but this administration’s labor board seems more determined to ban the use of the rat and other inflatable symbols. The cases are ongoing.

— Janice Gavin