The CSEA Nassau County Local 830 honored at its recent annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK Jr.) Luncheon members of our union family and community.

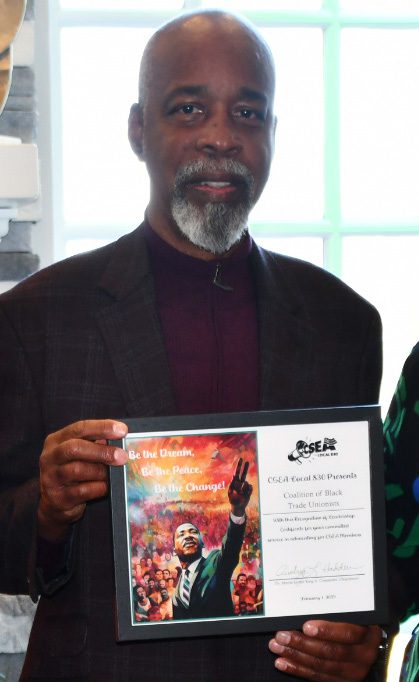

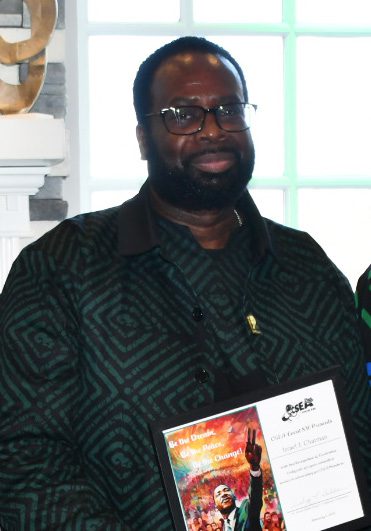

Nassau County Clerk Unit Treasurer Israel J. Chatman, Nassau County Local activist Garrett Wakefield, the Nassau County Guardians Association, the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists and CSEA Long Island Communications Specialist Wendi Bowie were among the special honorees. A special award was also presented to CSEA Long Island Region President Jarvis Brown.

The luncheon was coordinated by the Nassau County Local MLK Luncheon Committee, Nassau County DEI Committee Long Island Region Human Rights Committee. Nassau County Local activist Audrey L. Hadden chairs all three committees.

The luncheon also featured a musical performance, poetry, clips of Dr. King’s speeches and a DJ. It offered everyone an inspirational and festive opportunity to kick off the monthlong celebration of Black history and culture.

— David Galarza